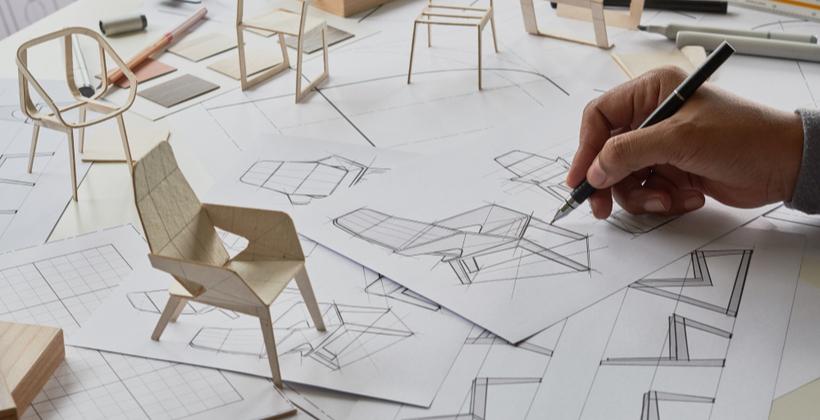

Design...design everywhere

I have ambitions to popularize sustainable living by overhauling our culture within product design. I realized some time ago the power of design to influence behavior: there is much that goes into a "design" that informs how people can and must interact with objects. The subtleties of how designs are understood by those who create them and those who interact with them comprise an entire field of study--usability. Don Norman expounds on the fundamentals of usability and the philosophy of design in his book Design of Everyday Things .

There is much covered in this book that I will allow you to discover for yourself. Instead, here I'll share a snapshot of my takeaways from the book--as a way of highlighting insights that I feel will serve as a stepping stone towards my ambitions, God-willing.

Mental Models

I was most impressed by the concept of "models" which Norman shares. For every piece of technology we engage with, we have a general understanding of the device's functionality. This understanding, regardless of whether or not it is accurate, constitutes our model for the device. Unpacking the role of these models and the means by which they are communicated is essential to Usability. Indeed, models are what allow us to figure out how I technolgy might function in situations we have never encountered before. (example. basic model for a lamp

For every device there is

1) The Designer's Model

2) The User's Model

3) The System Image

Designer's Model

The Designer's model describes a comprehensive and accurate understanding of how the device works. For an informed designer there is scenario in which the device's functioning would could them. The completeness of the designer's model is important to note. This completeness becomes an obstacle when engineer's and designer's seek to test the usability of their products themselves. They cannot accurately assess usability because they know too much to easily notice what might become major inconveniences to users.

User's Model

The User's model describes a learned understanding of a device that is only as thorough as their use of the device demands. Example, you may not know how all the buttons on your remote work, but you also don't care because you haven't ever had to use particular buttons. In order to appreciate the significance of models, we must understand that every action we perform relies on some combination of knowledge in the world and knowledge in our minds. When we turn a knob to raise some volume, we are combining knowledge in the world (some symbol indicating which knob controls volume) with knowledge in our minds (knowing that clockwise usually means louder). Every model we have is a composition, drawing from these two sources of knowledge. Therefore it essential for designer's to have an understanding of their users--and what knowledge they might already have in their mind--when determining how to communicate a sufficient model.

System Image

The system image is everything that users see and experience, and it is the central means by which designers communicate to users. It is through the system image that designer must share enough information for users to develop a sufficient model to use the device. Take an extreme example, imagine a device that could allow us to travel through time; the only problem is it look exactly like a rock--there are no handles dials, buttons, or screens--and it works only when you take it to precise geographical coordinates. No one would ever know how to use it, because there is nothing about the rock-looking, rock-feeling device that offers guidance on a reasonable model for using it. We know buttons are meant to be presses, handles are meant to pulled, speakers are meant to make sound, etc. Everything we use offers some clue as to how we should use it.

Whereas designers' model are a result of intimate knowledge of the technology, users' models are built in our interactions with devices. And there are so many clues that designer's incorporate to leverage users' psychology in developing the best mental model.

Visibility :

When something is visible on a device, it is an invitation for a user to devote some attention or action towards it. We can see buttons, handles, speakers, etc. By the same token, designers must also consider what should not be visible. Every laptop has a computer fan, however, knowing when the fan is spinning does not help someone use their computer better--it only distracts--so designers hide it. This principle of visiblity is especially relevant to controls. Devices are most easy to understand when there is a direct mapping of controls to actions. When one button controls more than one output, if it is pressed in different patterns for example, things tend to get confusing. There is a drawback here because devices with many many functionalities would quickly appear overwhelming if every function had its own button. The sweet spot in this case is to have a button for every function, but hide buttons when their controls are not in use.

Constraints :

Another tool that designers can leverage in improving user understanding is constaints. There are 4 classes of constraints: physical, semantic, cultural, and logical. Constraints offer guidance on what behaviors are impossible, weird, or non-sensical--thus contributing to the formation of an appropriate user model. If we return to the example of the TV remote, we see all 4 classes of constraints present. Physical -- actions that are physically impossible or extremely inconvienent give a clue that this action probably lies outside of what is appropriate use of the device. One does not pull on the buttons of a remote; there is no grip and the action is nearly impossible to do. Semantic--we describe semantic constraints as constraints born from context. We know that remotes are meant to control some out of reach object. Therefore semantic constraints would tell us that we should not expect to use a remote if we do not have a TV or other device. Cultural -- cultural constraints describes what falls in the categories "conventional", "standard", or "normal". When using a TV remote, you might look for the TV power button near the top/front of the remote becauses that's where the button "normally" is. Last we have Logical--logical constraints are simply what makes sense. If remotes cannot think for themselves, it would not make sense for us to expect a remote to change the channel before we've given the remote an input to change something.

Feedback :

Feedback is an essential tool that helps users build their model. Feedback offers an understanding of cause and effect. If I do this, this will lhappen. In some devices, everything is working and the user might be using the device as they're supposed, however, they are completely second-guessing themselves because the system is devoid of feedback to validate their actions.

Design Principles

Norman offers a succinct set of design guidelines:

1) Visiblity

2) Feedback

3) Affordance

4) Mapping

5) Constraints

6) Consistency

Make the appropriate features visible. Give informative feedback. Leverage intuitiveness. Map controls to functions. Take advantage of natural constraints. Be consistent.

I'll leave you with two thoughts that I feel make stand-alone case for everyone to learn more about usability design:

- "Any time you see signs or labels added to a device, it is an indication of bad design: a simple lock should not require instructions." -Don Norman

- "Technology may change rapidly, but people change slowly. The principals [of design] come from understanding of people. They remain true forever" - Don Norman